International Law and English Law

- Thomas Hibbs

- Feb 21, 2022

- 5 min read

Below is a piece published in Cambridge University publication Per Incuriam. See in full here: https://issuu.com/perincuriam/docs/per_inc_summer.

The piece responds to the question: ‘The rules governing the relationship between international law and English law do not promote compliance with the UK’s international obligations.’ Discuss.

I largely disagree with the statement. In Parts I and II, I discuss the rules regarding the incorporation of treaties and CIL into UK law. While the rules do not promote total compliance, they are sensitive to the nuances of domestic law, facilitating constitutionally legitimate incorporation. However, in Part III, I discuss the flaws in how the UK achieves compliance and suggest a new framework for the incorporation of international law into domestic law.

As a preliminary point, the UK has a duty to bring its domestic law in conformity with its international obligations, and failure of domestic law is not an excuse for failing to meet these obligations: as seen in, for example, Article 27 of the VCLT 1969.

I. Treaties

Observing the traditional approach to the incorporation of treaties, it may seem the relationship between international and UK law does not promote compliance. In JH Rayner, Lord Oliver deemed it ‘axiomatic’ that UK courts cannot ‘adjudicate on’ or ‘enforce the rights’ arising from treaties, ‘unless and until’ they have been incorporated into domestic law. Lord Templeman states in ITC that the government’s role is to ‘conclude’, ‘negotiate’ and ‘terminate’ treaties, whereas Parliament’s is to enforce the obligations arising from them in domestic law.

The rationale for the lack of direct effect is that the ‘Crown [cannot] alter the domestic law by… unilateral action’ (Arden LJ, Freedom and Justice Party). If all treaties were incorporated automatically, it would disregard the parliamentary sovereignty and the separation of powers; treaties are signed by the executive, so the automatic incorporation of treaties would allow the executive to, in effect, create law. The UK’s approach thus looks like a textbook ‘dualist’ approach, viewing international law as a separate and distinct system (Triepel, Azilotti), and leaving enforcement entirely to the whim of Parliament.

But this would be loose abstraction. The UK’s approach to treaties is far more nuanced: no direct effect is a mere starting point. Unincorporated treaty obligations can be adjudicated on where necessary for enforcing rights and obligations in domestic law (Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament), helping to satisfy the UK’s international obligations. Thus, there are several cases (Al-Jedda v Defence Secretary, Occidental Exploration v Ecuador) discussing whether the necessary ‘foothold’ in domestic law has been established to warrant intervention by courts. In Al-Jedda, this ‘foothold’ was provided by the HRA 1998, which indirectly incorporated the ECHR, allowing the House of Lords to use other treaties to determine the scope of ECHR rights (undertaking a detailed examination of UNSC Res 1546 and Article 103 of the UN Charter, where both were unincorporated in UK law). Furthermore, there is an interpretive presumption that Parliament does not intend to break its international obligations unless the statute is ‘clear and unambiguous’ (Diplock LJ, Salomon v Commissioners).

The rules on incorporation of treaties do promote compliance, but with sensitivity to constitutional principle.

II. Custom

Traditionally, custom is viewed oppositely, assuming automatic incorporation. This is because the test for CIL is ‘very demanding’ (FAJP): the executive cannot unilaterally create a customary rule. To this extent, custom seems more ‘monistic’, being incorporated as if international law were part of the same legal order (Kelsen, Lauterpacht) and satisfying compliance with international obligations.

However, again, this would be a position of abstraction. The best view following Trendtex is given by O’Keefe (2008): CIL is a ‘source’ of international law, rather than a ‘part’. This means that, as explained in FAJP, there is a ‘presumption that a rule of CIL will… shape the common law’ unless there is some positive reason of ‘constitutional principle’ why it should not (so, on the facts, special mission immunity in CIL was incorporated into domestic law).

This can be seen in three contexts. First, in R v Jones, Lord Bingham refused to recognise the crime of aggression in UK law because it has been well-established in common law that the courts cannot create new criminal offences (Knuller). Otherwise, it would allow the executive to ‘amend or modify’ the criminal law without Parliament’s consent. Second, in Chagos Islanders, Ouseley J rejected a claim for damages based on the UK’s alleged breach of the customary international human right not to be exiled from one’s home state, because it would amount to no more than a tort for unlawful administrative acts, which was not permitted in the common law. Finally, though the significance of this case is doubted by Lauterpacht and Collier, R v Keyn can be taken to support the concept that because Parliament had a right under international law to legislate the criminal law in their territorial waters, and had not done so, for the courts to intervene would be to ‘effectively [create] new law’ (Cockburn CJ). Constitutional principle demanded that Parliament legislated.

Thus, sensitivity to constitutional principle is the same as treaties, but with a different starting point—assuming automatic compliance.

III. A Better Approach

Despite my disagreement with the statement, I suggest that that compliance with international obligations can be better achieved. There are two problems with the current orthodoxy.

First, the differences in approach between treaty and custom are too stark. As Sanger (2019) notes, the presumption of different starting points overlooks that treaties can also be difficult to establish, and be as uniformly accepted as custom, such as the UN Charter. Furthermore, Nicaragua shows that the consent of all states (‘absolute rigorous conformity’) is not required to establish custom. Finally, the executives of (particularly western) states can exercise a disproportionate influence on the creation of CIL: indeed, this was Causee’s concern in his realist challenge to international law.

Second, particularly for treaties, UK law does not pay enough attention to the normative weight of the interest engaged. There is growing support for automatic incorporation of human rights treaties: Lord Steyn in McKerr suggested the approach needed ‘critical re-examination’. Sales and Clement (2008) present a stern defence of the orthodoxy, arguing (1) Lord Steyn misunderstood the rationale for the dualist theory. It is not that incorporation would risk executive abuses, but that the Crown cannot use prerogative powers to alter domestic law. Also, (2) rights are accompanied by duties, imposing financial burdens on citizens, and (3) burdens on the public purse.

My main difficulty is that it posits a very narrow conception of constitutionalism. It implies that Parliament, if it has not explicitly expressed its consent to a treaty, does not desire automatic incorporation. Yet one glance into, say, administrative law (Smith v Ministry of Defence, R v Jackson) reveals a richer conception of the constitution, with courts desperately concerned with giving greater attention to individual rights. Indeed, Feldman (1999) aptly notes that ‘constitutional legitimacy’ (the SOP and PS) is only one way to judge a legal arrangement, which can sit alongside ‘moral’ and ‘consequentialist’ concerns.

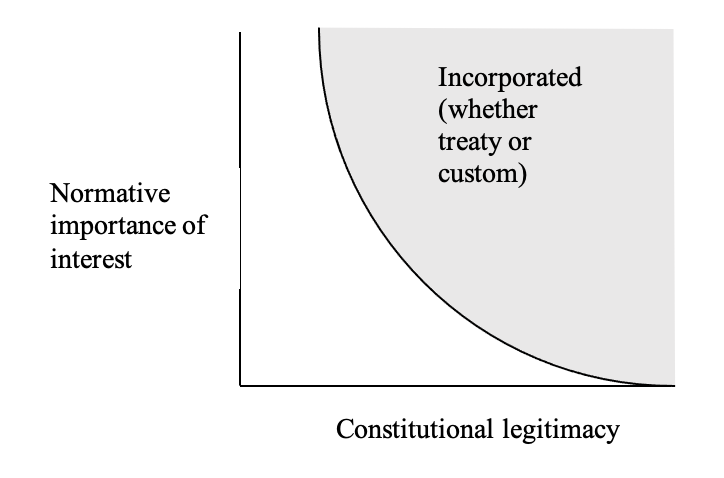

To address these two concerns, I suggest a more flexible approach to the incorporation of treaties and custom should be adopted, with traditional ‘constitutional’ concerns being considered against ‘normative’ concerns, including individual rights. This means treaties and custom are considered more closely than before, as well as giving attention to the possibility of, in the right circumstances, giving effect to the UK’s human rights obligations automatically. I have attempted to illustrate this with the diagram below.

IV. Conclusion

I have discussed that (i) the incorporation of treaty and customary law does promote compliance with international obligations, though with sensitivity to the domestic constitution; and (ii) suggested a new framework through which this could be better achieved.

Comments